â€å“these Come to Me Days and Nights and Go From Me Again

Taryn Simon, a lensman, shoots at the intersection of justice and visual memory to capture the desperate experience of men and women who accept been imprisoned because the latter misinformed the former. It takes a while to figure out precisely what Simon’s upwards to, but once her intentions unravel, you’ll discover yourself under the powerful spell of a very smart photographer whose obsession with the ambiguity of memory, contrasted with the concreteness of a criminal confidence, instills beautifully composed photographs with tragic weight. Then, if you’re annihilation like me, you’ll stay up all night, reading her book, staring at her photographs, and feeling thankful that y'all can walk through the door in front of you and use the bathroom in private. At to the lowest degree for now.

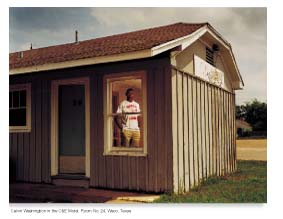

Simon’southward subjects have been wrongfully convicted and imprisoned by the U.S. criminal justice system. Most of them are black and Hispanic men who have suffered a Kafkaesque fate of unimaginable hurting due to visual memory’s unreliability. Photographs, lineups, blended sketches, Polaroidsâ€"identifications that rely on the assumption of precise visual informationâ€"contradistinct the form of their lives so thoroughly that fifty-fifty their subsequent freedom suffers nether imprisonment’s persistent and tumultuous influence. Simon’south examples are all-encompassing and impossible to summarize, simply one subject area, Roy Criner, served 10 years of a 99-year sentence for a 1986 rape and murder in Montgomery Canton, Texas. He says he â€Å"felt free†upon leaving prison but quickly found himself dogged by paranoia. â€Å"Who’s going to be around the corner tomorrow when I go to work?†he asks in an interview with Simon. â€Å"Sometimes I spit on the footing and say, â€Å"Well, maybe they’ll scrape that upwardly and put it on a crime scene. They had me ejaculate in a cup and said the vial got broke. They came dorsum and got blood and all this other stuff. You know there’s a lot of me that’southward however out there somewhere.†He wasn’t solitary in feeling this way. Tim Durham, who served three and a half years of a 3,220-yr judgement, tells Simon, â€Å"When I was released from prison I had considered developing a device that could be worn just similar a pager that could be used to track my movements.â€

For Simon, the testimony of victims like Criner and Durham transformed photography from an human activity that’southward still â€Å"cute in one context†into one that’s â€Å"devastating in some other.†That transformation would never accept occurred had it not been for the rigors of science. All of Simon’southward subjects were exonerated through the retroactive use of DNA prove. Dna is hard evidence, certainly more solid than the ambivalence of a medium like photography, whose about enigmatic quality is its precise ability to â€Å"mistiness truth and fiction.†And so it’south somewhat ironic that, to stress the fragility of the memorized imageâ€"a fragility intensified past its use in the criminal justice systemâ€"Simon resorts to the very aforementioned activity that stunted her subjects’ lives in the kickoff identify: capturing an image. Nevertheless, her photos freeze her subjects’ painâ€"you’ll detect that it’south surprisingly difficult to stare in the face of the wrongfully accused and convictedâ€"with more than rawness and emotional heft than science could allow. And that too, I suppose, has an irony all its own.

Which brings me to what, in the most general terms, I really like about this book. Photographers who show in contemporary galleries, those who accept a tendency to think of themselves every bit â€Å"art photographers,†frequently indulge in bouts of brainy conceptualism. Especially when they’ve graduated from places like Brown University, as Simon did in 1997. But Simon never succumbs, taking instead a refreshingly pragmatic, photograph-journalistic, and even muckraking bending into her cloth. I was just waiting to roll my optics at an obligatory window-dressing reference to the philosopher Michel Foucault in the â€Å"Photographer’s Foreword,†but instead I found Simon’south short essay soberly summarizing the direct social implications of her work. â€Å"The high stakes of the criminal justice arrangement,†she writes, â€Å"underscore the importance of a photographic image’s history and context.†Simon wants her portraitsâ€"many of which are shot at the scene of the misidentification, arrest, alibi location, or crimeâ€"to recast the criminal investigation in a broader lite, one diffuse but bright enough to appreciate the potentially lethal inconsistencies inherent in the available evidence. Subsequently she shot a few such photos for a New York Times Mag story in 2000, she secured a Guggenheim grant and traveled across the country expanding her portfolio of personal devastation. Perchance the most obvious result of her research and work, which was first displayed earlier this summer at P.S. 1 Contemporary Arts Eye in Queens, is the egotistical realization that information technology inspires: â€Å"This could happen to me.†It’due south a sentiment that any reference to Foucault’s Bailiwick and Punish would merely have mocked. Her work, at its cadre, is stripped of all pretension and imbued with a physical political goal.

Some other aspect of Simon’s book, though, demands more clarity. While most of her subjects are black men, and speak openly nearly the racism behind their conviction, Simon herself handles the glaring question of race delicatelyâ€"perhaps too delicately. Her reticence is especially evident in the case of Jennifer Thompson and Ronald Cotton wool. Thomson, a white woman who was raped by a blackness homo in July 1984, accused Cotton of committing the crime. Cotton wool served 10 and a half years of a life judgement. Her recollection of the allegation is, in many respects, honest and revealing:

I picked out the olfactory organ, the eyes, and the ears that most closely resembled the person who attacked me…From the composite sketch a phone telephone call came in that said the sketch resembles someone they knew: Ronald Cotton fiber. Ron’southward name was pulled and he became a key suspect. I was asked to come down and look at the photo array of different men. I picked Ron’s photo because in my mind it most closely resembled the man who attacked me. Merely really what happened was that, because I had made a composite sketch, he actually most closely resembled my sketch as opposed to the actual attacker….I picked out Ronald because in my listen he resembled the photo, which resembled the composite, which resembled the attacker. All the images became enmeshed to 1 image that became Ron, and Ron became my attacker.

In terms of the connection between photography and â€Å"erroneous eyewitness identifications,†Thompson’s testimony hits the nail on the caput. But upon reflection, the excerpt obscures as much every bit information technology reveals. It’s impossible, for case, not to wonder about the racial assumptions hiding behind Thompson’due south accusation. To what extent did the pervasive stereotypes of blackness menâ€"stereotypes deeply woven into the Southâ€"(the rape occurred in North Carolina)â€"shape both Thompson’southward initial composite sketch and her ultimate photo identification of Ronald Cotton wool? â€Å"In my mind†is a telling phrase and one that she says twice during the extract. What racial assumptions does that qualification entertain? Could Ronald Cotton have conformed to Thompson’due south preconceived notion of a black rapist rather than to her memory of the traumatic incident?

I’m aware that these questions are complex, not to mention charged, but a photograph of a hulking black man with his arm draped around a dainty Southern belle whom he allegedly raped demands that the issue at least be addressed more direct than the perfunctory mention of â€Å"cantankerous-racial identification.†And when a black man like Clyde Charles, wrongly bedevilled of a 1981 Louisiana rape, recalls â€Å"en women and two men, all white jury…The D.A. told me he didn’t intendance if Santa Claus did it, he was going to captive me for it,†the demand for a more than explicit focus on race by the author becomes that much more apparent.

But what The Innocents shirks in terms of race it more than compensates for in its brutally honest exploration of the unexpurgated emotional responses to false incarceration. This book is, in many ways, an angry i, and Simon deserves much credit for allowing her subjects to practice most of the talking. And boy do they have something to say.

â€Å"What ten years of life would you want gone?†asks Eric Sarsfield, who served nine and a half years of a x-to-xv-year sentence. â€Å"1 to ten? Ten to twenty? Twenty to thirty? …You feel like somebody owes you something. But nobody has nothing for you.†Ronald Jones, who served 8 years of a death sentence, seethed, â€Å"You’re not gonna come across no rich people on death row, very few of them even go to jail…as long equally I’m poor, the same affair that they did to me in 1985, they can do it to me over again.â€

â€Å"United Snakes, I mean States of America,†says Warith Habib Abdal, adding, â€Å"’scuse me, my teeth are loose. They kicked them out in Attica when I was busted for rape.†Walter Smith, who served 12 years for robbing a gas station, explains, â€Å"I’one thousand going to get mine . If y'all come at me, come right. Because if you’re wrong, I’thou going to go you.†Marvin Anderson lost 15 years of his life to the system but insists, â€Å"I still believe in the law 100 percent.†But, he adds, â€Å"I don’t believe in the people who enforce the constabulary. They’re human and do some muddied things.†The litany of bitterness goes on and on. And then it’south refreshing to come up across Verneal Johnson’southward testimony. â€Å"The day I was released,†he says, â€Å"it seemed similar the lord's day came down close to the globe and just started shining. It was the happiest day of my life. I just stood outside under the dominicus. It was a beautiful dayâ€"went and ate me a hamburger and got me a Budweiser.â€

After reading this amazing book, you may very well want to do the aforementioned, savoring your freedom while lifting a Bud in celebration of not only Johnson’south freedom merely of Simon’s beauteous debut.

Contributing writer James McWilliams lives in Austin.

Source: https://www.texasobserver.org/1493-book-review-picture-yourself-here/

0 Response to "â€å“these Come to Me Days and Nights and Go From Me Again"

Postar um comentário